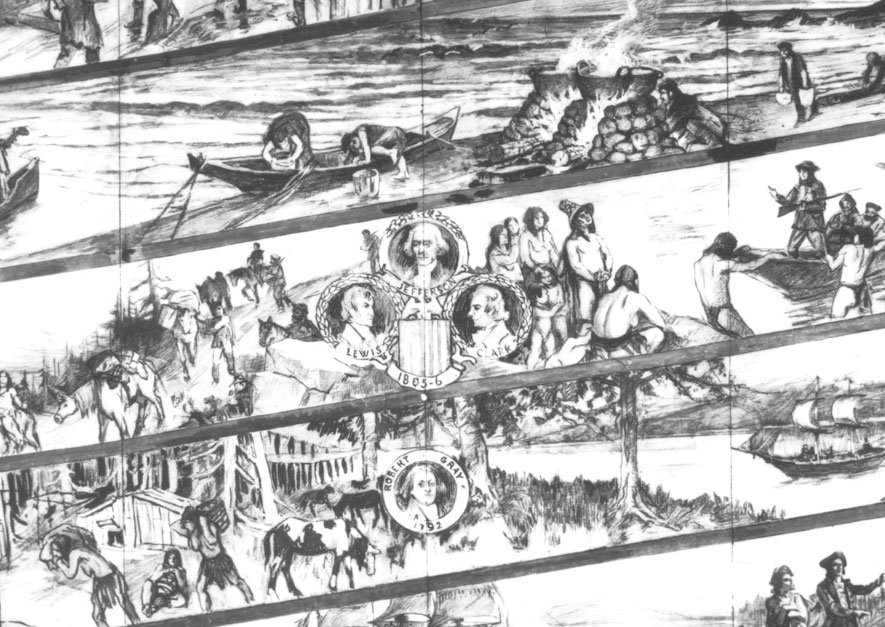

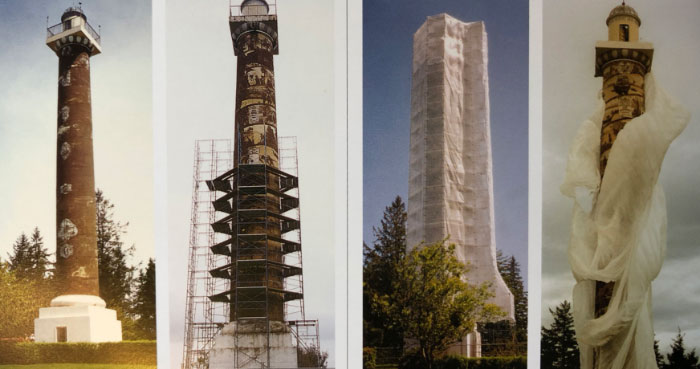

The lengthy process of transcribing the artwork onto the Column’s surface allowed only three bands of images to be completed by July 22, 1926: dedication day. However, the unfinished exterior did nothing to dampen the enthusiasm of the 8,000 celebrants who enjoyed three days of festivities to mark the Column’s dedication. Attendees included loggers performing log-rolling, bathing beauties, a boxing match, five U.S. Navy ships, street dancers, bands, choirs and the “Prunarians” of Vancouver, Washington.

Following the festivities, Pusterla and his assistants got back to work and the artwork on the Column’s exterior was finally completed on October 29, 1926. It was the first use of sgraffito on a monumental column.

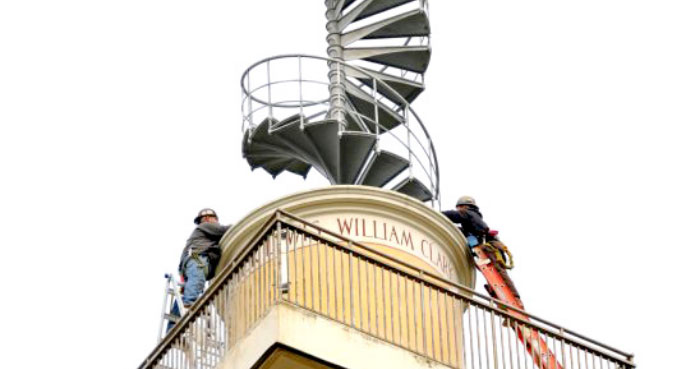

Astoria vs. Astor Column: Officially, the name of the monument is the Astoria Column, as it was dedicated in 1926. Ralph Budd believed that naming the monument the Astor Column would focus too much attention on the contributions of Astor, while diminishing those of Astoria’s early explorers—Captains Robert Gray, William Clark, and Meriwether Lewis.

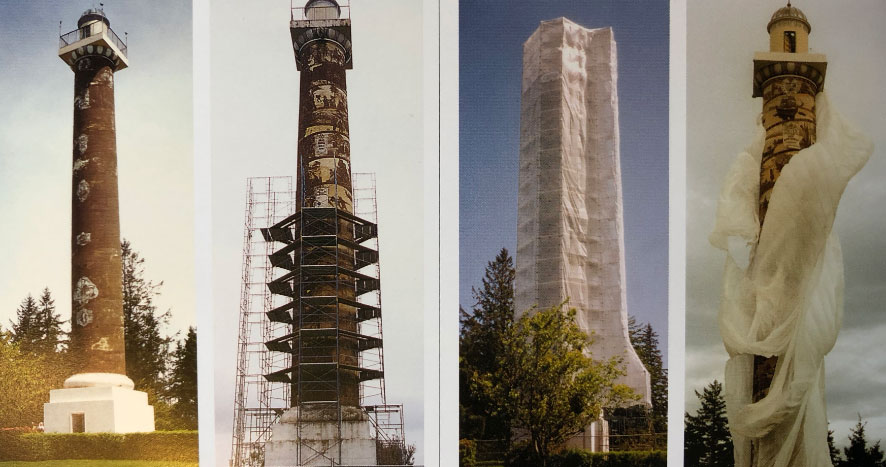

Top: Dedication day, July 22, 1926.

Bottom: Visitors to the Column in late summer or early fall, 1926; Pusterla’s progress on the mural can be seen in the background.

PHOTOS COURTESY THE CLATSOP COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY